Agent Scully, Oppenheimer, and the Philosopher’s Stone

|

I want to believe that my fascination with atomic science began with Kevin J. Anderson’s X-Files spin-off novel, Ground Zero, published in 1995. My Dad, the avid sci-fi-thriller fan that he is, had read it in paperback while our household was in full-on Mulder and Scully fan mode in the 90s. After it spent quite a while sitting on the back patio, aging rapidly in the Florida heat, I finally picked it up and read it myself.

The FBI agents get involved in a case of a singularly bizarre death, in which a nuclear weapons researcher is killed in what appears to be a miraculously small-scale atomic blast in his laboratory. Two more seemingly unrelated deaths occur in similar fashion, and of course, Mulder suspects some connection, which SPOILER ALERT turns out to be the ghosts of people who were utterly neutralized by the nuclear tests done in the 40s and 50s being directed by a survivor to annihilate certain individuals responsible. It’s a fantastic piece of fanfiction, and if it didn’t set me on my path of interest in all this nuclear history, I don’t know what did.

|

| Still in my library |

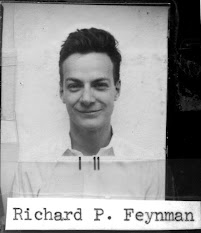

Then came the subsequent honors physics class in high school, which whet my appetite further, and the physics in college and the post-secondary nerd pursuit of particle physics e-books about Rutherford, Bohr, Heisenberg, Dirac, Dyson, Fermi, Einstein, etc. I picked up histories of quantum physics at the library. I had Prof Brian Cox and all his BBC presentations. I read Kaku, Tyson, and Hawking. Hearing audio recordings of Richard Feynman describing the batshit antics he got up to at Los Alamos while he was part of the Manhattan Project drew me in further. I even read Schrödinger, FFS.

While reading Feynman’s most groundbreaking lectures on Quantum Electrodynamics (QED—a field in which he won a Nobel prize in 1965), I felt for about five minutes at a time that I actually GOT it. I could see how all this led to the computerized world we know today. We categorically wouldn’t have the digitized universe we take for granted without all this particle/quantum research. And through it all, there was always the dark reminder of the price paid for this modern promethean fire kindled in that New Mexico desert. A radioactive specter permeated everything ever since.

J. Robert Oppenheimer was the philosopher scientist, with his heart split between the humanities and science. His theoretical physicist buddies poked fun at him for wasting his time with philosophy and literature and poetry and learning languages, but these things rounded him out. Of all the great “luminaries” in the desert, he was most qualified to open the world’s eyes to the dual-edged sword of atomic energy. He was deeply fascinated by the physics, but he was grounded in ethics schooling as a child, and being of both worlds gave him pause when it came to nuclear arms. He’s was the ideal scientist: one who thought deeply about the repercussions and responsibilities of discovery. But even he couldn’t help getting caught up in the fervor of his government’s rage to end World War II at any cost. It plagued and haunted him for the rest of his days.

Feynman said about winning the Nobel that “the prize is the pleasure of finding things out.” He abhorred “honors” as he called them; they were mere epaulettes—empty signifiers of “expertise” or power. He was also haunted by the result of working on the Manhattan Project and was happier later in life to see his work in the quantum theory field be applied for good. QED has led to the development of medical imaging, lasers, and microprocessors, among many other useful applications.

But another iconic (albeit fictional) mathematician once said “What is so great about discovery? It is a violent, penetrative act that scars what it explores. What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world.” Dr. Ian Malcom, the resident “chaotician” of Jurassic Park (1993), warned against the dangers of genetics just as Oppenheimer did about nuclear weapons, and both were ridiculed for speaking out. Although Oppenheimer also closely parallels InGen founder John Hammond. They both opened Pandora’s box with their respective scientific enterprises, both in an effort to do something good for the world, and both made an about-face when it proved more problematic than they had anticipated.

These connections clearly did not go unnoticed by the Jurassic Park filmmakers, as there is a prominently displayed photo of Oppenheimer taped to the chaotic computer programmer Dennis Nedry’s computer monitor.

In 2021, when I visited New Mexico for the first time, I joined my family on a day out at White Sands National Park, situated south of the site where the Trinity test was conducted in 1945. We also made a trek out to Roswell—a pilgrimage that would have made Mulder proud. In fact, there’s a chapter in Ground Zero where Mulder and Scully stop at the “historic” Owl Bar and Café for burgers before they have to catch their flight in Albuquerque. Mulder makes a joke about making a side trip to the famous alien crash site, and Scully picks up a souvenir at the café: a piece of greenish rock she saw in one of the dusty glass display cases. She tells Mulder it’s trinitite—sandy glass not created by any geologic process, but by a “man-made inferno that had lasted only a few seconds.”

At the end of an episode of The X-Files in 1997, Scully tells Mulder why she thinks he gave her an Apollo 11 commemorative keychain for her birthday:

“I think that you appreciate that there are extraordinary men and women and... extraordinary moments when history leaps forward on the backs of these individuals... that what can be imagined can be achieved... that you must dare to dream... but that there's no substitute for perseverance and hard work... and teamwork... because no one gets there alone... and that, while we commemorate the... the greatness of these events and the individuals who achieve them, we cannot forget the sacrifice of those who make these achievements and leaps possible.”

The Trinity test and the launch of Apollo 11 both occurred on July 16th, 24 years apart. In a quarter of a century the United States had gone from a Pyrrhic victory in a hot war to a giant leap for mankind in a cold one. We contain multitudes.

|

| As a keychain collector, I am very jealous |

While perusing the oddball stores and alien-themed establishments in Roswell, I ducked into a rock and gem shop, as I am wont to do. There, I soon spotted a glass display case that held my quarry: little lumps of trinitite. I promptly purchased one—which would have made Scully proud. She was my childhood scientist idol after all, and the first of many in the years to come. She was the ideal—a rational, clear-minded medical doctor, but also a contemplative human being wary of things being taken too far in the name of “science.”

|

| A tiny piece of history |

This trinitite in my hand is its own Philosopher’s Stone. It’s the byproduct of an ultimate scientific achievement, wrought by years of single-minded dedication and hard work, but is also the object that alchemizes a sense of wonder into one of elemental terror.

Oppenheimer’s favorite Shakespeare play was Hamlet, and he named it on a list of ten books that most shaped his philosophy of life. In a spell of literary alchemy, I imagine he would have picked out these disparate lines and fused them in his mind:

What a piece of work is a man…

…the enginer hoist with his own petard.

Comments

Post a Comment